Abolish Homework

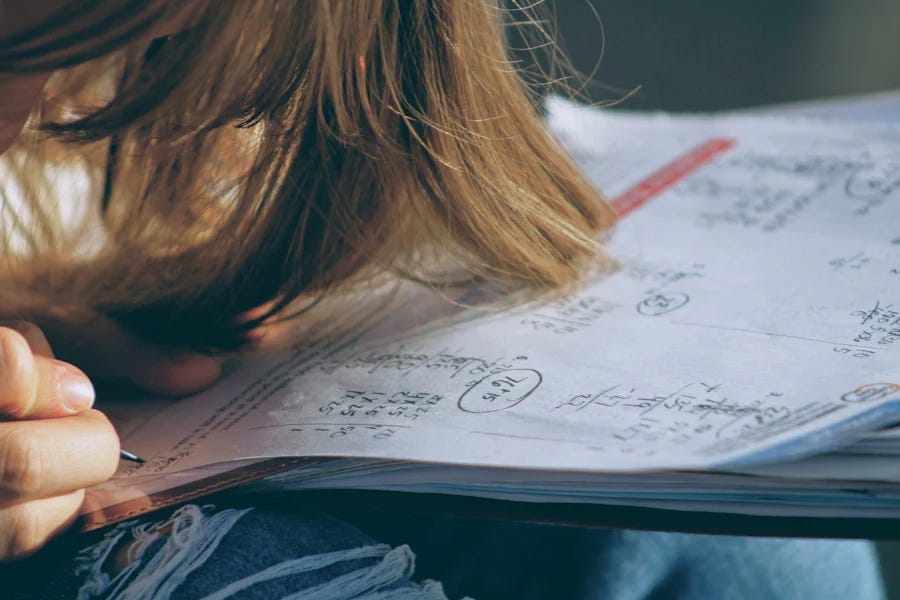

It does nothing but stress students + moms + teachers out, and it's bad for families

This letter is free for you to read, but it wasn’t free for me to write. It would mean so much to me if you could take a minute to prayerfully discern becoming a full subscriber. Our full subscribers keep the lights on, but they also get access to our entire archives, summer read-alongs, Q & As, and whatever else my faithful feminist brain dreams up. If you want more essays on Catholic feminism, upgrade your subscription.

I love the beginning of the school year. The smell of freshly sharpened Ticonderogas; the clip of Tupperware I’m tucking sandwiches into; the sight of that bright yellow school bus turning the corner to greet our long neighborhood line of wiggly littles. I love hearing what my kids learned about that day and I love learning their friends’ names and I love field trip chaperoning and I love seeing which library books they carefully selected.

But I do not love homework.

At back-to-school conferences for each of my kids’ teachers, they kindly asked if we had any questions. K shot me a look, as if to say: it’s you. Of course you have questions. And I do—questions about discipline, questions about the social studies curriculum, questions about how often read-aloud is. But one question I always take a quick, hopeful inhale before is, “can you tell me about what homework looks like in your classroom?”

My kids are in elementary school, for a bit of context. This year, I have a third and first grader. Both of their teachers gave me the same answer, which was 20 minutes of reading a night1 and a math worksheet with occasional spelling words to practice.

“Okay,” I said. “And what would it look like if that homework didn’t get turned in?”

“Oh, like if there was a soccer game or something?” one asked. “No problem. I’d just ask for it to be brought the next day.”

Now, K is really looking at me, please-please-please be gentle, which—I am! But that’s when I give my spiel. About how I was raised by public education and really respect it, hence why my kids attend a public school. But I’m a bit of a homeschooler in a public school mom’s body. I’ve done a lot of research about homework from a wide variety of sources. And I don’t think homework is helpful or a priority, meaning we will mostly be choosing to “opt out” of homework this year.

Or, as my third grader likes to gleefully tell his friends, “I don’t do homework because my mom doesn’t believe in it.”

I was raised by a teacher. My mom was a fifth grade educator in the public school system for 35 years before becoming a literacy coach. And she was, for all intents and purposes, ahead of her time in her educational mindset. Homegirl was teaching her fifth grade kids to make butter like a tradwife in 1999. She would take her classes camping. She would read aloud from chapter books long past when kids could read on their own. She eschewed homework and grades and skill-level-based groups (the “smart” reading group and the “dumb” reading group, and yes, kids know which group they’re in!) as much as she was possibly able. She was extremely popular as a teacher and to this day, we’ll be walking around the zoo or the children’s museum with her and someone will approach her all excited because she taught them a bajillion years ago. And there was one education guru she loved more than any other: Alfie Kohn.

This name will mean absolutely nothing to a lot of you, but Alfie Kohn is an educator and author who specializes in a type of educational theory that doesn’t utilize rewards, punishments, or hard-and-fast grades. (My mom gasped in horror when she saw our sticker chart congratulating our kids on new Polish vocab; let’s just say sticker charts were not a thing in my childhood. She’s going to gasp in horror again that I’m about to publicly share that we used to have to have our progress report cards signed in middle school and she straight up told me to sign it for her because she was sure I was “doing fine”. I literally can not remember a time I was asked “how did your test go” until the ACT. But I was brought to every museum, monument, and historical landmark in the country and given an endless supply of books.)

I’m not a teacher, but I’ve long been interested in theories about education—mainly because I’m a mom, and I think moms are their childrens’ first teachers no matter which schooling system you discern is best for your family. Last year I read The Homework Myth by Kohn, and it gave numbers to things I’d long felt in my gut were true.

Read the book, but here’s the TLDR: homework is not helping our kids in school.

There’s never been a statistically-significant study showing that homework in the elementary school years leads to improved academic performance. But there are studies showing that homework leads to decreased attitudes about school and learning.

There are so many studies in the book that it would be impossible to lay them all out here, but one example is from researchers Gerald Letendre and David Baker. Not only did they fail to find any positive relationships between homework and academic achievement, but “the overall correlations between national average student achievement and national averages in [amount of homework] are all negative.”

Kindergarteners—five year olds! Who don’t even go to school in many countries!—are receiving an average of 25 minutes of homework per night.2 So many little kids, who had to spend most of their day getting those little brains filled with exciting new information and sights and sounds while trying to sit still for longer than is likely developmentally appropriate, have to come home now and go through spelling flashcards.

What homework might slightly help increase are standardized test scores, but to quote Kohn, “There does seem to be a correlation between homework and standardized test scores, but (a) it isn’t strong, meaning that homework doesn’t explain much of the variance in scores, (b) one prominent researcher, Timothy Keith, who did find a solid correlation, returned to the topic a decade later to enter more variables into the equation simultaneously, only to discover that the improved study showed that homework had no effect after all, and (c) at best we’re only talking about a correlation — things that go together — without having proved that doing more homework causes test scores to go up.”3 And that’s all assuming you view standardized tests as a valid way of measuring academic achievement, which I do not.

When I told my kids’ teachers this information—like I do every single year, as delicately as I can—they usually respond with, “I know! If it was up to me, there wouldn’t be homework, but the parents ask for it. I barely even look at it.” And while at first this infuriated me—GUYS, IT IS QUITE LITERALLY UP TO YOU—I can certainly understand the pressure teachers are under from so many different sides. Administration. Parents. Other teachers. Culture. I’m empathetic to their situation but at the end of the day, we need to make this information known and get rid of pointless worksheets once and for all.

So what does any of this have to do with Catholic feminism?

Homework isn’t just pointless. It’s bad for families.

Time is a zero-sum game. What you use on one thing, you’re unable to use on another. When kids are coming home from long days of school and sat down in front of worksheets, worksheets that do nothing to further their education or help them actually learn, that’s less time they have to play outside. Less time they have to read books of their own choosing that they actually want to read. Less time to sleep. Less time to talk to their parents and siblings. Less time to make up games with the neighbors. Hell, less time watching TV—and while we can wring our hands about screen time and childhood obesity, both of which are surely things to be worried about, I would rather my kids veg for 30 minutes in front of Lego Batman before hopping up to build a lego world versus spend 30 minutes wrestling through word problems.

Many teachers I know follow the “10 minute rule”, meaning each grade level should have 10 minutes of homework (10 for first graders, 20 for second graders, 30 for third graders, etc.) That may not seem like much. But think of a sixth grader. They’re eleven years old. Say they get home at 3:30. They are children, ie., they need a snack and a few minutes to just be. Say they also have soccer practice for an hour. Then dinner with the family. So, by now, it’s 6:30, and they need to do an hour of homework. By the time they’re done, it’s 7:30, giving them—what? An hour and a half of time to be an actual human being? To read, and create, and tell their parents about their day, and hang out with their friends, and help out around the house? They’re eleven, and they have to come home from a long, exhausting day of school work to do an hour of worksheets?!

“We might forgive the infringement on family time if homework were assigned only when there was good reason to think that this particular task would benefit these particular students, that it will help them think more deeply about questions that matter and create more excitement about learning (and that it can’t be done at school). But what educators are more likely to say is, in effect, ‘Your children will have to do something every night. Later on we’ll figure out what to make them do.’ If there’s a persuasive defense of that approach, I’ve never heard it.” - Alfie Kohn

Furthermore, homework puts unneeded stress on both parents and teachers. I’ve literally never met a teacher who said they had free time on their hands, and I as a parent know firsthand the annoyance that sitting down to go through a math worksheet brings on. It causes friction in the home over a completely arbitrary thing with no benefits that doesn’t need to exist!

I believe in teaching kids responsibility, and there are one or two smaller studies that do show an increase in “responsibility” with increased homework. Things like this asinine document from the Florida Department of Education claim that homework does things like “teaches students how to problem solve” and “gives parents a chance to see what is being learned about in school.” But did it ever occur to them that there are so many ways to teach these lessons by simply existing in a family? Having kids help make dinner or keep their rooms clean are both able to teach responsibility while actually contributing to a family goal (nutrition and cleanliness). There are a thousand ways to naturally teach kids responsibility that don’t involve sticking them on the busywork assembly line at age six. And if parents what to know what is being learned about in school, they could ask their child or email their child’s teacher. Many teachers produce a weekly newsletter detailing their units—the idea that we need worksheets to teach us what our kids our learning is nonsense.

Instead of forcing elementary schoolers to push their brains further than they need to go by having them do endless math problems after school, which it begs repeating has never been shown to increase math skills, we could be incorporating them into family life and enjoying being with one another, something which actually leads to better outcomes in life.4 We could even be encouraging their natural love of learning, by exposing them to books and documentaries and museums on topics of interest instead of rote memorization of facts or spelling words.

I’m not a gentle parent. I’m not a helicopter parent. I’m not a crunchy parent. My parenting does not have a trendy label; we are living on coffee and a prayer over here. I believe in letting my kids do hard things and fail and struggle. But doing hard things should have a point. And that point shouldn’t be “let’s suffer and struggle because my teacher feels like they need to give me ten minutes of math homework every night so Riley’s mom doesn’t call and complain.”

Last week my sister-in-law texted me a photo of a note that had been sent home with my first grade niece. It read: “You’ll notice I don’t assign any formal homework. That’s because while studies have failed to demonstrate that homework leads to greater academic success for kids, many studies have shown the benefits of eating dinner together, reading bedtime books, and playing outside. Please do those things with your child instead and let me know if you have any questions.”

The revolution is here, one first grade teacher at a time.

All right, hit me in the comments—I know some of you are screeching in disagreement. Tell me your homework theories and what homework looks like in your house!

On My Nightstand

Trump Has Abandoned Pro-Life Voters: As a rule of thumb, I always read Patrick T. Brown. I enjoyed his latest on how Trump has abandoned the people who put him into office.

iThink Therefore iAm: A really interesting piece on technology’s transformation of the human experience and political networks. “Digital space has dissolved the horizontal relations of our lives as relentlessly as the vertical, leaving us all ‘alone together,’ in Sherry Turkle’s phrase. Although platforms constantly hold out to us promises of ‘community’ and ‘connection,’ the very use of such nostalgic words, as Anton Barba-Kay argues, belies the absence of any real bonds. One can always opt in or opt out, mute or block, delete an account or create a new one: Why waste time talking to a bore? No longer defined by a community of belonging, we are free to define ourselves, curating and creating our own identities through the content we post, the filters we apply, the avatars we adopt.”

Kamala Harris and the Progressive Black Elite: Smart take on why blackness isn’t the best way to group a radically varied group of people. “Because Blackness has historically been treated as monolithic, informed by a shared experience of persecution and marginalization, scholars and policy makers have long ignored the Black elite and its central role in America’s racial landscape.”

In case you missed these Letters:

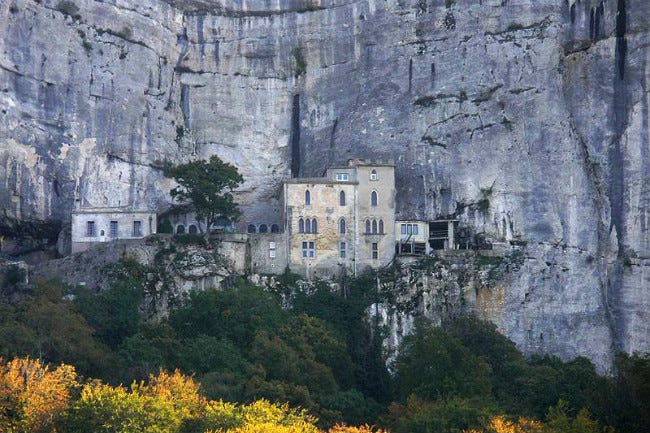

Bonjour! Want to join us in France?

In October 2025, I’m leading a pilgrimage to the south of France: the Way of Mary Magdalene. We’ll be traveling to Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, where the remains of St. Mary Magdalene are, as well as other sites associated with women in the gospels. We’re also sipping wine, visiting Cannes, wandering Aix-en-Provence, and so much more. This isn’t a vacation, mission trip, or retreat, but a true pilgrimage, where we’ll journey together and grow in our faith. Sign up today! ❤️ (And PS: if you’re thinking, “wow, Claire’s mom sounds like a badass”, she’ll be there!)

This is too long of a ramble for this particular letter but: I also don’t force my kids to read. They do it on their own, for at least an hour every night. I know that’s not everyone’s story or season but I would strongly argue that creating a culture of reading in the home and consistent read alouds are going to do more for a child’s literacy than forcing them to sit on the couch while an egg timer counts how long they have left in See Spot Do His Mountain of Pointless Busywork.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01926187.2015.1061407

https://www.alfiekohn.org/blogs/homework-unnecessary-evil-surprising-findings-new-research/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4325878/

I didn’t know there was someone championing this, but I’m hopping on this train. Growing up, my mom always advocated for less or no homework, and as an adult, I see why.

Our younger kids go to a public Montessori school with no homework. I adore Montessori for a thousand reasons, and no grades/homework is most definitely one. The older ones have transitioned to a traditional school in middle/highschool without any problems, but the no-homework approach in the younger years fosters a genuine love for learning and time/space for family, creativity, and boredom - all necessary! Joining you in fighting this battle for all kids because the data is real & families don't need one more stressor on their plates. Yes, we need widespread educational reform but it ain't coming from worksheets and workbooks. Good for you for saying no.